Adapting PBIS to an online education context

Did your classroom move online? How do you maintain Positive Behaviour Interventions & Support in a virtual environment? Can PBIS be used to make virtual education, just like in a brick and mortar school, more effective?

With the unknown duration of the pandemic and rolling closures of schools across the world, teachers and educators face the complexities of delivering classroom instruction in a virtual learning environment. How do you maintain a consistent approach to classroom management when there is no face-to-face teaching? In this article we wish to convey that it is possible to maintain a high degree of behavioural integrity in a virtual classroom, just as you would in a regular classroom, by keeping in mind one of the key principles of Positive Behavioural Interventions and Supports (PBIS): focus on building pro-social and self-management skills.

We will share some guidelines and prevention strategies teachers and educators can do to keep behavioural expectations you had established prior to the pandemic. These guidelines and steps are also useful if your school is not working via the framework of PBIS, and can also be used to elevate student engagement and maximize student learning under these unprecedented conditions. During this time of uncertainty, students may well appreciate the structure established. Most of these guidelines and prevention strategies can also be found on the website of www.pbis.org or https://www.pbisapps.org/Pages/Default.aspx. Check out their valuable resources.

1. Use video conferencing

This guideline may seem trivial, since everybody is known nowadays to be zooming, team-ing and meeting virtually with these online platforms to connect with each other. Video conferencing provides video and audio connections to keep the entire class together and allows teachers, students, and also parents to engage with each other, in real-time. Also, it allows structured activities, just as in a real classroom, by planning break out rooms and by putting comments in the chat to everyone, or to someone privately.

2. Be mindful of 'Zoom fatigue'

But we have a warning for you: these video calls are likely tiring out teachers, students, and parents. Video conferencing have skyrocketed, and the possibility that you can use video, does not mean that you have to. A recent study of Bailenson (2021) identified four causes for Zoom fatigue: 1) excessive amounts of close-up eye contact is highly intense, 2) seeing yourself during video calls constantly in real-time is fatiguing, 3) video chats dramatically reduce our usual mobility, and 4) the cognitive load is much higher. For each Bailenson has an advice: 1) minimise face size by taking Zoom out of the full-screen option and use and external keyboard to allow more space between oneself and the grid of faces staring at you, 2) use hide self-view button by right-clicking on your own photo, 3) turn your video off periodically during meetings to give yourself a brief non-verbal rest, and 4) take an audio-only break to turn your body away from the screen. These pieces of advice can be put in the behavioural expectation matrix developed for virtual teaching.

3. Involve and engage parents

Parents can be the ‘eyes and ears’ of the teacher when your students are having remote learning. Parents need to understand the behavioural expectations for online schooling. Collaboratively develop a behavioural expectation matrix for online learning, possibly integrated with behavioural expectations that families can use at home. These can be aligned to the school-wide values and expectations. Offer webinars for parents to make sure that they understand the expectations of virtual schooling and discuss with them how they can communicate with their child and collaborate with the teacher. Keep lines of communication simple, easy and open, and acknowledge that parents need to know that the teacher is there to support their child. And of course, be mindful of ‘Zoom fatigue’.

4. Working towards behavioural integrity

Set and establish virtual-classroom expectations, just as in a traditional face-to-face classroom. Teach those expectations regularly, just as in a real classroom. Model and teach those appropriate virtual learning behaviours. Develop and share video-clips of students engaging in expected and appropriate virtual learning behaviours. Virtual behavioural expectations that require explicit teaching and clear guidelines and procedures are, for instance:

- Signing in on time for virtual class and meetings

- Checking in at designated times

- Creating an appropriate home workspace

- Logging study times

- Participating in a virtual classroom

- Collaborating and discussing in virtual dialogue

- Taking turns respectfully in a virtual workspace

- And, of course, how to cope with 'Zoom fatigue'

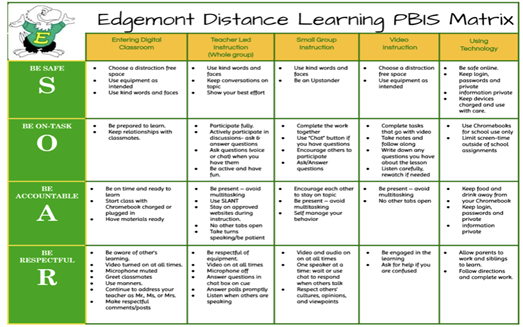

5. Create a PBIS behaviour teaching matrix for virtual learning

Just as in a real classroom use a behaviour expectation matrix to make virtual learning safe, predictable and positive. This is important to define, teach and practice the behaviours teachers and families want to see, especially virtually. It is important to stress that online interactions are just like real-life interactions, with the same positive and negative consequences for behaviours. Steps for developing a remote instruction teaching matrix can be found in this practice brief of the Center on PBIS. Here is an example of Edgemont Elementary School:

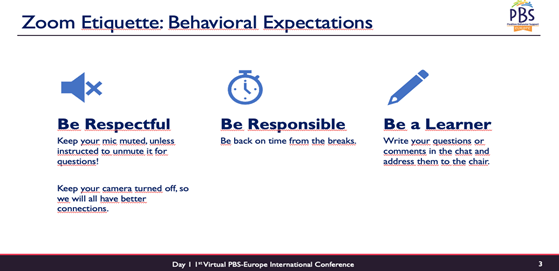

Here is an example we used for the 1st International PBS Europe Conference in November 2020.

6. Create a system of accountability

Students need to know the positive and negative consequences of their behaviour in a virtual classroom. So, just like in a face-to-face classroom design and built in a foundation of accountability that is predictable, transparent and consistent.

7. Reinforce behavioural expectations

Teachers can reinforce behavioural expectations by establishing a system of tangible reinforcement via a so-called point system, a token economy to reinforce and track student behaviour. There are tools to do this real-time via Google Sheets in order to quickly award points, track them, and for students to easily redeem them. However, this can be challenging for the teacher to monitor, so the teacher can also consider setting longer-term rewards for when the students return to a real classroom. Then it is necessary to provide more social reinforcement than you typically would do in a regular classroom to keep students engaged.

8. Provide behavioural feedback and social reinforcement

Provide students with instant feedback on their virtual behaviour, by using the chat function when signing in on time or checking in on the designated times or giving them a virtual heads-up, and tallying that on a Google Sheet. It is important to communicate directly to students.

9. Provide behaviour intervention as necessary

If students are not meeting the virtual behavioral expectations, deliver constructive feedback to them by again communicating directly with students, either via whatsapp or via simply calling them. In addition to this, it may be necessary to share concerns with parents and request their support. The teacher can also consider deducting points from the token economy, but this should be done carefully and the ratio 5-to-1 positive to negative interaction ratio with students needs to be taken into account.

10. Use and share student data

Track positive learning behaviours and responses. Share them with your students and make them insightful and transparent by creating a spreadsheet for each student to share via Google Classroom or Google Sheets.

11. Be mindful of equity

Some students may receive a lot of parental support, while others can learn and work independently. Also, some students can experience unreliable internet or have only one device for all children in the family. When a student has choppy internet do not blame or exclude the student for that, but follow up with the student after class. Some households can experience limited internet bandwith and the challenge with parents working remotely and all children streaming video conferencing.

12. Make sure all staff are teaching these prevention strategies, creating routines to ensure they occur

Like in the face-to-face classroom, explicitly teach prevention measures by using ‘prompt – teach – reinforce’ and tie these practices to the school’s current school-wide values and expectations. Encourage families to engage in similar prompting, teaching, and reinforcing at home. The teacher can organise a webinar for parents to practice this.

Most of these guidelines and prevention strategies are based on the information on the website www.pbis.org or https://www.pbisapps.org/

Sui Lin Goei, Jeroen Pronk & Wilma Jongejan

VU Amsterdam, Netherlands

References

Lee, A., & Gage, N. A. (2020). Updating and expanding systematic reviews and meta-analyses on the effects of school-wide positive behaviour interventions and supports. Psychology in the Schools. doi:10.1002/pits.22336

Bailenson, J. N. (2021). Nonverbal Overload: A Theoretical Argument for the Causes of Zoom Fatigue. Technology, Mind, and Behaviour, 2(1). https://doi.org/10.1037/tmb0000030