Augmented Reality can help students with dyspraxia find stability

Every child deserves to have a great childhood and to be able to experience things, such as riding a bike or playing some kind of sport or other physical activity.

Furthermore, they should have the ability to interact with the world around them.

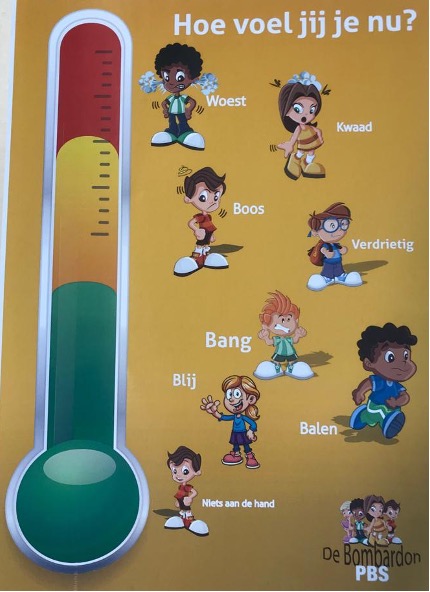

However, children with the condition known as dyspraxia may find these tasks quite difficult in contrast to their peers, and may become demotivated and wonder if something is 'wrong' with them, when really, they are simply differently wired. In fact, many people with the condition have brilliant long-term memory and heightened creativity.

Like Autism, dyspraxia operates on a spectrum, meaning that no one diagnosis is the same as another. Research suggests that it predominantly affects males, with an estimated 70-90 per cent incidence rate, but it can also affect females.

Overall, dyspraxia is estimated to affect around 5 to 6 per cent of all children, with different degrees of severity.

Even before a child is diagnosed or is believed to have the condition, a tremendous amount of effort on behalf of the carers, medical professionals and educators goes into implementing strategies that will enable these children to function to their full capacity in all of their environmental settings.

For both young children with dyspraxia and educators, being able to function in a classroom environment can prove to be a huge challenge. Thankfully, lessons are becoming more inclusive for all types of learners and educators are more aware of what they need to do in order to make sure all their students succeed to their potential capabilities.

One article- which utilised a variety of sources from organisations such as The Dyspraxic Foundation, The I-CAN Training Centre, and the Hampshire Educational Psychology Service - outlined other tasks that children with this condition may struggle with:

Acting and thinking simultaneously (to name a few examples: tying shoelaces, writing, playing a ball sport.)

- Co-ordinating the precise movements of the lips, tongue or palate in order to pronounce certain words

- Understanding messages that the senses convey and difficulty in relating those messages into actions.

- Planning and organising.

- Difficulty in feeding.

Children with dyspraxia do not deserve to be left behind or to feel like an outcast, especially in school. It requires a tremendous amount of effort for to create effective strategies to help children with this condition. Practicing skills on a regular basis can help many of these children overcome some of their diagnostic characteristics.

Studies suggest that technology involving the use of Augmented Reality (AR) can help students with dyspraxia to overcome some of problematic areas. Although a relatively young form of technology, AR already has a notable history of supporting users with disabilities. For example, apps that utilise AR have helped those on the aforementioned Autism Spectrum to recognise facial expressions and to help them recognise social cues. It also helped them to create reliable work schedules, something which many children, regardless of their academic learning abilities, benefit from.

A study that was revealed at the 2018 Fifth International Conference on eDemocracy & eGovernment, investigated how AR could help students with dyspraxia with balance and motor skills. Using a game known as ATHYNOS, it found that it was able to help children with the condition 'to be more engaged in physical training and improving their bodily-kinaesthetic intelligence, taking into account that children are digital natives.'

Areas which dyspraxic students greatly improved in included: motor skills, hand-eye coordination, bilateral integration, and sequencing - all of which are common problem-areas for many of those on the spectrum.

In addition, language apps have helped children with this condition to improve the way that they pronounce words, as well their overall understanding of language and phonetics.

They were able to practice both eye contact and communication skills thanks to the use of AR, which helped them memorise and learn repetitive behaviours, as well as visual aiding cues to help with dressing and personal hygiene.

It should be noted that AR alone is not enough to help dyspraxic children in overcoming their problems. Rather, there should be a multi-disciplinary approach, including: counselling, speech therapy, regular meetings between parents and teachers and the implementation of relaxation techniques.

Breaking the stigma is important for these children in order to interact, engage and communicate. AR supported lessons can be tailored to support individual needs. Early identification and intervention are critical to enable children with dyspraxia to be able to live fulfilling lives, and not to be defined by the condition.

By Ciarán Mather